My Grandma Was a Fed - Lessons from Digitizing Hundreds of Hours of Childhood

In Which I go into Great Detail About Digitizing Video8 and Learn My Grandmama Lived With a Prostitute

I was in my basement on my birthday, cleaning out our cluttered utility room, when I first noticed the plastic tub near the furnace. This bit of tidying up was in order to install a squat rack I’d just bought from a fellow father off Facebook Marketplace - apparently mid-life crises do hit at exactly 40 years old.

I’d forgotten entirely about this container, but the tightly-sealed white lid stood out in a room half-full of boxes with mangled cardboard flaps barely keeping them closed. I knelt down, released the snaps on each side, and lifted off the lid, revealing rows upon rows of neatly stacked video tapes.

You notice when someone is filming you. It’s only human nature to recognize when your appearance and behavior is being captured forever. This is true even in a world where everyone carries a video camera in their pocket. It was even much more true in my childhood, where film cameras were commonplace, but video cameras were a rarer sight.

No one told my father this - well, they did, and he didn’t care - because he loved his Sony Handycam Video8, and it became a ubiquitous part of our family gatherings. I’d forgotten this until I saw those tapes, mostly because it was part of the background of my childhood, Dad setting up the tripod in the corner of the room while he taught us to play card games or we decorated the Christmas tree.

The tub was almost completely full. I later counted 122 tapes, and found out this format could capture about two hours per tape. What was in those 200+ hours of my childhood? My mother’s handwriting gave me partial answers: Steven Play, Emily Recital 1993, Grandmama and Papa Thanksgiving, etc.

I noticed that as time went on my mother’s regard for posterity diminished. It soon became “Fall 1996”, and then just “1998.” What happened in 1998? I couldn’t access a single memory from that specific year, but I knew that strip of magnetized tape would bring them back. Curiosity flared.

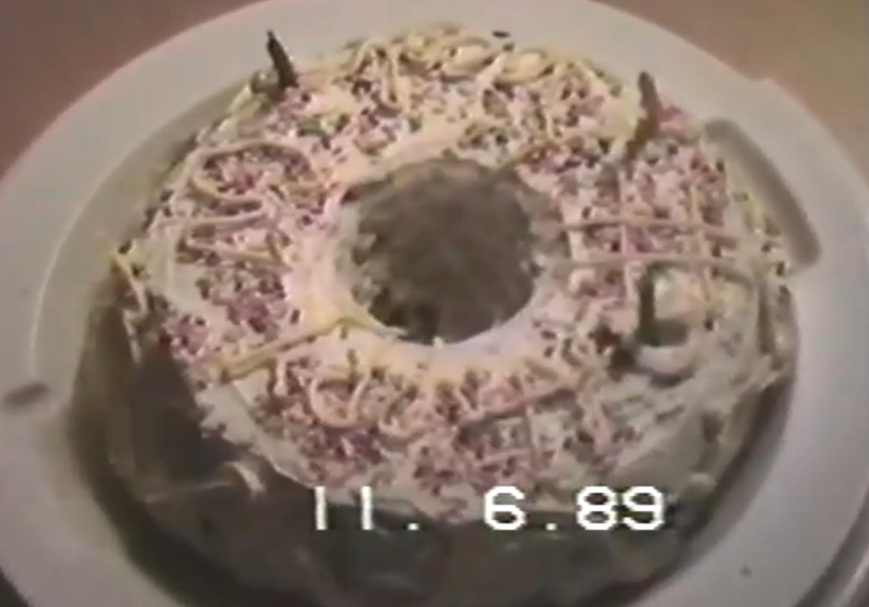

One thing my mom may have wished we’d forgotten. In 1989 she self-deprecatingly proposed we create an ugly cake award in honor of her baking triumphs. Believe it or not, this was the runner up.

My mind kept coming back to those tapes as I continued cleaning. I opened another tub, this one containing letters I’d received in my later teen years. Those were difficult years for me, and I started to put the tub aside, deciding not to risk invoking a depressive form of nostalgia. But the curiosity sparked by those tapes hadn’t diminished, and I reopened the tub.

Do you remember the good things about the bad parts of your life? If so, congratulations, you’re more gracious (or have a better memory) than I. The low points are most vivid. But, if we’re fortunate, even - and especially - in those times we have people trying to help create some good things for us. I’m a bit ashamed to say I’d forgotten those people, and those things, and this tub was full of them. I was overcome with the wonderful realization of just how many supportive friends and family I had.

All of us tell ourselves stories about our own childhoods. How accurate are they? Historians know that the further away in time from the primary source, the less reliable the story. Other than parents and siblings (and perhaps a smattering of childhood friends), there’s almost no feedback to validate our own stories. And those other people also rely on memory, and are also afflicted with the same human foibles that lead us to not have entirely trustworthy stories of the past. Magnetic tape has no such flaws.

Siblings! I have three, and I imagined each of their reactions to unearthing hundreds of hours of childhood video. What stories did they have, and how might these tapes interact with them? And my own? I couldn’t know, but I suspected that it was closer to the “wonderful realization” end of the spectrum than the “depressive nostalgia.” Bolstered by those new positive memories, I decided I must digitize and share those tapes.

I searched for services which offered to digitize Video8 tapes. Most services cost about $20 per tape. Even with discounts for bulk amounts, it would likely have cost about $2k! I considered paying it (how exactly do you value a few hundred hours of childhood video?) but then I noticed how they delivered the videos - a private media hosting solution for 60 days. I knew this would be a huge amount of data, and only giving me and my siblings two months wasn’t sufficient.

I was curious about the possibility of doing this myself, and I asked ChatGPT. Not surprisingly, it knew a lot of the various tapes, file formats, sizes, processing, storage, and after it asked some clarifying questions, it was quite optimistic about me being able to do this myself. In typical sycophantic fashion, it reassured me that I was very technical adept, knew how to create websites, owned a 4090 GPU, and already had a homelab operating. If I set up good processes, I could save a lot of money and also have way more control.

I started researching digitizing the tapes, watching YouTube videos and talking to ChatGPT, taking notes about the main areas I needed to focus on. One of the most important things I learned was that in order to digitize the tape, it needed to play in real-time as it was captured.

I quickly realized the implication - this wouldn’t only be a big project logistically, but would also take a very long time. Capturing the tapes would be a few hundred hours alone, then I needed to convert the tapes into a format that can be shared online, create any metadata about the videos, determine local storage, online storage, and determine how to actually share the videos with my siblings. I stopped the research for a moment to create a timeline.

It was early September, so there were about four months until the end of the year. If I did one tape a day, I could nearly get the 122 tapes completed by then. I decided to aim for Christmas and make this a gift for my siblings. But this would mean I had to start now. Like, now now.

Digitizing these tapes requires a camera that can play Video8. Of course we didn’t have one of those, that’s a very old format. I started looking online before it struck me: we still had what was left of my parent’s possessions elsewhere in our basement. I ran downstairs.

I found the black and red camera bag in no time. My father’s camera was still there, the same device which recorded the ~20 years of videos. I plugged it in, and it lit up promisingly. I pressed the eject button in order to insert a tape, and… nothing. I did the full gambit of hopeful button pressing, to no avail, only to have ChatGPT dash my hopes for good when I asked for help.

It turns out that this is an exceedingly common problem on old Handycams, especially if they’ve gone unused for many years. The only realistic fix is to send it to a specialty repair shop, which tended to cost a few hundred dollars, and even then you weren’t sure how long it might last.

I was disappointed. It would have seemed appropriate to use the same camera to record all these memories, again. But ChatGPT gave me a silver lining - now that I needed a new camera, I could make this whole process much easier on myself by getting a slightly newer model which supported FireWire.

The old camera was entirely analog and the interface from the camera to a computer to record was somewhat convoluted, but with a newer camera from the early 2000s it would allow me to download raw .dv by plugging a FireWire cable into the camera and running it to… wait, FireWire? That’s ancient, I can’t plug that in anywhere! Even if I could, the operating system probably wouldn’t handle it anymore, right?

Somehow I made it 1,300 words without mentioning that I’m a Linux user. And yes, FireWire is still supported in the Linux kernel. All I needed to do was buy a FireWire card and plug it into a PCI-Express slot. It cost $22 - my first purchase so far.

My next purchase wasn’t so cheap. I needed that “new” Handycam, and it turns out there’s a bustling market for these for exactly the reason I wanted it. They’re hot items for people doing video capture. I found quite a few cameras which were the right model, but nearly all of them clarified that the tape heads weren’t new and not guaranteed to be clean either. Everything I read said it was imperative to get solid heads, so when I saw a Sony DCR-TRV740 on Ebay that claimed to have new clean heads, I made an offer, he countered, and I bought it for $249.

I was too impatient to wait for delivery, and I noticed he lived in Michigan as I do, so I selected local pickup. Only when I checked the location did I realized he lived on the other side of the state. A more patient man would have sent a slightly embarrassing message on Ebay asking for delivery and figuring out the additional payment, but I couldn’t shake the vision of popping in a tape and seeing scenes no one had watched for ~20+ years. Tonight!

Three hours later I met a young man in the parking lot of a housing development “youth center.” He held out a cardboard box and politely asked for me to release the payment. I asked to see the camera operating - $249 isn’t chump change - and he looked around, no outlets in sight. But he popped his trunk and had an inverter in there (clearly a pro), plugged it in, and handed it over.

I had brought along two tapes, ensuring that 1) this camera played this format of tape, and 2) this camera worked at all. I don’t remember exactly which tape I popped in, except that I saw my mother as she looked when she was around my age now. She passed away in 2013 at 55 years old, and I hadn’t seen her at this age in… well, I don’t know how many years. I released the payment.

I had already exchanged a few question with this young man, and I told him about my project. He let me know that 120 tapes was way more than I could reliably capture without at least one cleaning along the way, and explained you could buy a cartridge to do this before we parted ways. Helpful guy.

I got home and popped in some more tapes, and each of them worked, even the oldest ones from the 1980s. The FireWare card and cable was still shipping, so I began to work on the pipeline. I initially thought I would just dump the raw file to my local SSD and then convert to an MP4 and figure out a way to share the file online. But the more I considered this approach, the less I liked the idea.

For one thing, each MP4 file was likely to be about 3GB. It’s not trivial to share a single file that size, and sharing 100+ is a real headache. Also, it’s not easy to watch a file like that. You’d need to download the entire file first to even be able to watch it.

Perhaps more importantly, would you even want to watch that much video? I had been so excited to see these memories that I still wasn’t taking in the scale. If you watched 8 hours of tapes a day, it would take nearly a month to get through them.

I could just imagine my siblings looking at a list of hyperlinked filenames, eyes glazing over. When they randomly chose T084.mp4 and spent 5 minutes downloading it, they’re met with 45 minutes of a church play from 1994 and an hour of carving pumpkins on the dining room table. Few would have the wherewithal to persevere and find the nuggets of nostalgia within.

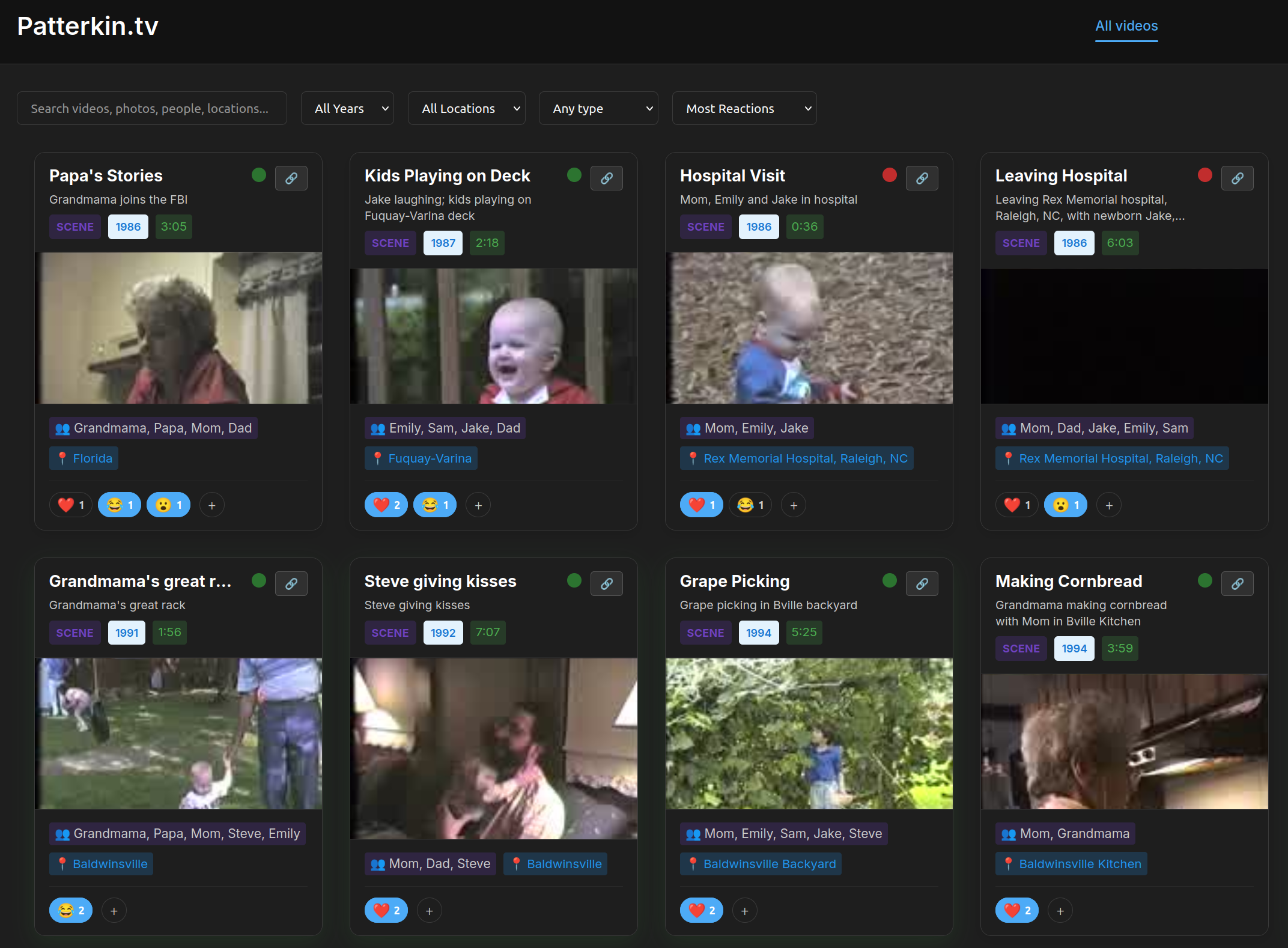

The solution was clear: the tapes needed to divulge their secrets. If I captured the metadata about the videos themselves, then me and my siblings could decide what was worth watching and what could be skipped. When watching the tapes, the most obvious way to structure this data was right in front of me: chronological scenes unfolding one after the other. I planned to record the beginning and ending timestamp for a scene, along with who, when, where, and a description of what happened.

Conceptually this made a lot of sense, but I was unsure of the most practical way to do this with so much video to go through. I didn’t want to sit through all the videos and manually write down timestamps. I looked into AI, and found some promising leads. AI segmentation and identification models are getting very good, but unfortunately the versions you can run locally aren’t the best, and the sheer amount of video was impractical.

The FireWire card arrived, and I took my PC apart in order to plug it in. My 4090 takes up a comical amount of space inside my tower, but after some maneuvering I have it installed, and I power up the PC and the camera.

Linux doesn’t disappoint me. It recognizes the camera and with the help of some commands from ChatGPT, it starts capturing the first tape. I stop it after a few minutes to watch the footage, and my heart sinks.

It’s not tracking properly. This is one of the biggest problems when capturing from analog devices, tracking is finicky and can be difficult to solve. I notice that the tracking goes off during scene transitions. I try a different command, and this time it works fine.

It turns out that the dvgrab tool on Linux supports auto splitting scenes by default, as well as remotely operating the camera over the FireWire. I thought this feature would be convenient, because it allowed me to pop in a tape and then start capturing by running a script. However, for an unknown reason, if I used the remote camera controls and had auto split on, it would lose tracking on scene transitions.

Once I figured this out the capture worked perfectly. It meant I had to press a button to start capturing on the device, and it meant the blank gaps in between scenes would be left in the capture. I could live with those compromises.

The first full tape finished and produced a 26GB .dv file. This turned out to be a slight problem for the default video player in Ubuntu, which couldn’t easily move around a file so large. It kept getting stuck and crashing. I installed VLC and that fixed it immediately.

VLC was a godsend, because it solved my metadata problem. I didn’t know this before, but you can create your own VLC plugins. It turns out that ChatGPT is good at writing them. I told it that I wanted a timestamp tool where I could hit a hotkey and it would record the scene start time, then when I hit the hotkey again it would record the scene stop time and give me input fields for people and a video description. Each scene was written to a text file in the video directory.

This worked perfectly. I later added the ability to adjust the timestamp based on the video start time. Most videos had several seconds of blank time before the capture started so it would adjust the timestamp based on the delay input.

I created a YAML metadata file with everything needed and then dropped the scene information into a freeform notes section, then prompted an AI agent to format the scene information to make it proper YAML. AI is really good at formatting text; this saved me so much time. Later I add a script to convert to JSON to make it easier to use online.

But it did still require me to watch the videos to find the scene start and end, enter in the dates, people, location and describe what happened in the video. Even hammering the right arrow key to skip ten seconds in VLC, this is still the single most time consuming part of this project.

Spoiler alert: it’s February and I’ve gotten through 64 tapes so far. I’m skipping ahead a bit here, but I build a platform to share these videos and I’ve shared it with my siblings already, so I’ll just keep uploading videos until I get through them all.

I now consider what else I need. I love captions. I watch most video with captions on. This is great for viewing, but when I consider it more deeply I realize that if I transcribe all these videos I’ll have a text record of a significant portion of our childhood. I later find out this was a great idea; there are multiple videos of my parents talking in great detail about our family history with their parents and one grandparent. There is a wealth of information about genealogy in those transcripts.

Obviously I cannot do this manually; this is already consuming a lot of my time. It’s the perfect job for an AI transcription model. I talk to ChatGPT about my options, and we settle on using WhisperX. I’m quite familiar with running AI models locally, and before long I test it on a full clip. It works beautifully, and only takes a few minutes for an entire two hours.

If I want to share these videos and scenes online, I’ll also need to pull some images out of them. Browsing text isn’t nearly as compelling as seeing a preview of the video itself. I write a script with ffmpeg to pull a frame from ten seconds in the video and include it in the processed output folder as a poster image. But when I test it, I realize a randomly chosen time doesn’t work well. The image is too random. So I allow the script to accept a flag with a timestamp. It’s fun to find the best time in a video to represent it.

A single image isn’t good enough though, because there are many scenes. I decide to make a sprite image, which take tiny thumbnails of frames at certain intervals and stitches them together into a single image. Then when sharing the scene the website can display just the portion of the image for that scene (closest timestamp).

We still have a 26GB raw .dv file. The first video processing step is to create an archive MP4. This is the file that will be processed further down the pipeline instead of working with the huge raw file. It takes 6-7 minutes to convert the entire file using ffmpeg.

I still need to decide how to share these. I could have dropped them on YouTube, but I don’t like the idea of Google having all my family’s memories. Once I began to create the metadata I already knew what I wanted to do: create my own streaming platform for our family’s memories.

I don’t know anything about streaming video, but ChatGPT does. It explains HTTP Live Streaming (HLS) and how to convert the archive MP4 to be streamable. Basically, it chops the video up into hundreds of very short videos and create a list of them. Your browser looks at the list and plays each of them in order. This means you don’t need to download the entire video in order to begin watching, you can seek around without much loading time, and you can also switch video quality depending on how fast your connection is.

This pipeline is getting long! I decide to bundle it all into a single master script. Once the raw file is done being captured, I watch it to record timestamps and other metadata, finalize the metadata YAML with AI prompting, and then run the script. It create the archive MP4, the transcript, poster image, sprite image, HLS videos, and the metadata JSON. This is everything I need for streaming. You can view the details of the script here:

But I run into a problem: storage. Not only do I not have enough of it, but moving these large files to my NAS is painstakingly slow, sometimes taking half an hour to move a file. I don’t have any choice either, my SSD only has about 100GB free space, which is only 3-4 raw videos, and I can only process videos from my SSD, so I need to move everything as soon as it’s processed.

I log into my NAS box and notice the CPU is running hot. This is an old machine I got at an electronics refurbishing store. It’s worked well for many years, but it only has a 1GB network adapter and the CPU is struggling to handle moving files this size.

I know I need to upgrade my NAS, soon. A new machine entirely. Fortunately, I have a much newer PC that was my daily driver for many years. It has 2.5GB network and a beefy CPU. I decide to buy a 2.5GB network adapter for the old machine, solely to make transferring files between them faster.

Once everything arrives, I buy two 10 TB drives and put them into my new NAS and install TrueNAS. Everything works, and I go to test moving files from my main PC. Uh oh, it’s the same speed as the old NAS! Was this all a waste?

I talk with ChatGPT and we run some network diagnostics. It turns out that my router was throttling my local network traffic. I buy a simple network switch, and this solves the issue. Where the old NAS took 20 minutes to transfer the new NAS takes less than one minute.

Now local storage is solved, but online storage is still an open question. I eventually settle on using Cloudflare’s R2 object storage combined with authentication from Supabase. This allows me to ensure that only authenticated users can access the videos, and it’s fairly cheap to host a few terabytes of video that aren’t being frequently accessed.

I’ve never used Cloudflare workers before, and the documentation isn’t the best, but eventually I have it working and build the UI to allow my siblings to log in and view the videos.

I run the script on a raw video, check that it all works, then run the upload script, and boom! Our childhood videos are now streamable.

Something is missing though. Yes, it’s awesome to browse the videos this way, seeing different random scenes of your childhood. But there’s no story unfolding there. I decide to build a timeline which is personalized for each sibling - since each video has metadata about who is in the clip, and when the clip was taken, you can watch yourself grow by just scrolling your own timeline.

Of course having the ability to react and comment on videos was next - too many good memories to now allow us to express ourselves when watching them. With Supabase logins this wasn’t too hard to implement.

Lots of work in getting the video search, filtering, caching, etc. I keep watching videos and making metadata, uploading then finding improvements to the UI. It’s becoming a bit tedious, but sometimes I find little gems in the videos themselves.

Wait, did my Grandmama just say she worked for the FBI?!?! And lived with a prostitute?!?!?

In September 1986, my grandparents were telling stories of their youth to my parents. My papa was just describing how to was involved in the 1952 loss of the USS Hobson, a real tragedy. Then my grandmother talks about working in Washingon DC in the late 1940s.

She always was hilarious. I don’t doubt that she did disconnect half of Washington in those two weeks as a switchboard operator.

Time to publish this for real: My wife created some Christmas cards with usernames and passwords for my siblings and their spouses. On Christmas day, we spent the morning with my youngest brother and his wife, and I showed them the site. He cast it from his laptop to the TV, and we had a great time scrolling through videos and sharing memories. My wife and kids had never even seen me as a child before, in video.

The site is now live for my siblings, and I’m considering making the code open source for other people to use themselves. It’s quite a bit of work to set it all up, but it should be fairly easy and cheap to maintain as a family archive for many years to come. It cost me $2.75 for storage in January. Once all the videos are uploaded, it might be $5 a month.

There are many small details about getting this to work that I’ve left out, because it was already getting far too long - if you’re interesting in tackling something like this yourself, feel free to reach out, I’m happy to share about my experience. My email is in the About page.