No Longer 98.6 - How Human Body Temperature has Changed

In Which I Learn that our Body Temperature is Lower than Commonly Believed

I came across a comment on Hacker News the other day that intrigued me:

Average “healthy” body temperature is down more than half degree exactly because of reduction in inflammation. People used to have very unsanitary lives and were fighting infections nonstop. 37.0C was the “normal” body temperature when the “norm” was first discovered in the early XIX century, now it’s considered to be a sickness already.

I would credit the author, but I saved the text to review later and now I cannot find the thread - there aren’t good search engines for HN comments either.

I’ve never heard this before, and it sounded fairly easy to confirm. I asked OpenAI’s DeepResearch to weigh in on this, and it gave a thorough response.

The bottom line: The claim appears to be accurate, although there’s definitely uncertainty in a two key areas:

- Were previous measurements accurate enough?

- If there has been a decline, why? (several proposals below)

Summary

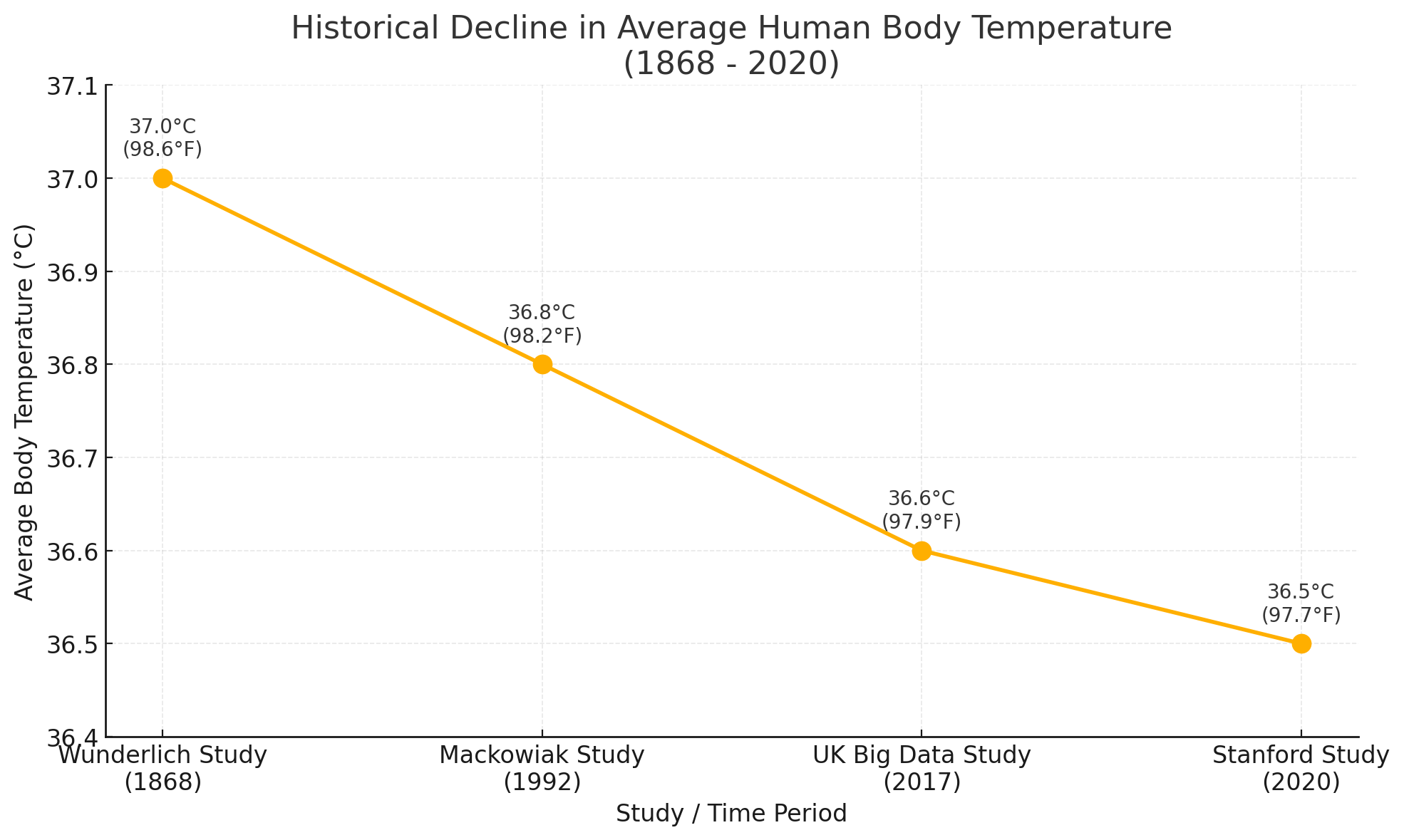

Historical and recent evidence indicates that the average human body temperature has decreased approximately 0.5°C (about 1°F) since the 19th century, dropping from the traditional 37°C (98.6°F) established by Carl Wunderlich to about 36.5–36.7°C (97.7–98.1°F) today. Studies, including extensive analyses of historical data, confirm a genuine decline likely linked to improvements in public health, reduced chronic inflammation and infection rates, and more stable modern living environments. Consequently, contemporary medical guidelines now define “normal” body temperature as a range rather than a fixed number, emphasizing individual variability over a single universal standard.

Investigating Changes in “Normal” Human Body Temperature (1800s–Present)

Introduction

For generations, 37.0 °C (98.6 °F) has been taught as the “normal” human body temperature. This value originates from 19th-century measurements and became medical dogma. In recent years, however, scientists have questioned whether 98.6 °F is still an accurate average. Evidence from modern studies suggests that the average body temperature of humans may have declined over the past two centuries 1 2. This report reviews the historical basis for the 37.0 °C standard, examines contemporary research indicating a downward trend in body temperature, explores proposed reasons for this decline (especially the role of reduced infections and inflammation), and compares how “normal” body temperature has been defined in medical literature from the 1800s to today.

19th-Century Origins: Wunderlich’s 37°C Standard

The notion that 37°C (98.6°F) is normal comes from German physician Carl Reinhold August Wunderlich’s seminal work in the mid-19th century. In 1868, Wunderlich published Das Verhalten der Eigenwärme in Krankheiten (“On the Course of Temperature in Diseases”), reporting the results of an extraordinarily large survey of patient temperatures 12. Over several years he collected over one million temperature readings from about 25,000 patients in Leipzig, using axillary (underarm) thermometers 3. From this massive dataset, he calculated that the mean healthy human body temperature was about 37.0 °C (98.6 °F) 3.

Wunderlich described not just a single value but a range of normal variation. He observed healthy adults’ temperatures typically ranged roughly 36.2–37.5 °C (97.2–99.5 °F) under resting conditions 3 4. He also documented predictable daily (diurnal) fluctuations – lower in the early morning and higher in late afternoon – and noted differences between populations: for example, women tended to have slightly higher normal temperatures than men, and older individuals ran slightly cooler than younger adults 4. In Wunderlich’s assessment, the body “maintains itself at the physiologic point: 37°C = 98.6°F” under normal conditions 12. He even considered temperatures up to about 38°C (100.4°F) as the upper limit of normal in healthy people 5. Above that, one would be considered febrile.

Wunderlich’s meticulous approach and enormous sample size made his findings hugely influential. By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, medical texts widely adopted 37°C (98.6°F) as the standard normal body temperature 6 12. Importantly, Wunderlich’s original data and writings show he understood normal body temperature is not one fixed number, but rather an “average” with natural variability 4 12. However, the convenient number 98.6°F entered the popular imagination (and many reference books) as the normal temperature, usually without elaborating on the underlying variability.

Modern Evidence of a Decline in Average Body Temperature

Starting in the late 20th century, researchers began to question whether the long-held 98.6°F benchmark accurately reflects modern humans’ temperature. A pivotal study in 1992 by Philip Mackowiak and colleagues reappraised Wunderlich’s legacy. They measured oral temperatures in a group of healthy individuals and found an average of about 36.8 °C (98.2 °F) – slightly lower than 37.0°C 7. Their analysis, published in JAMA, argued that 98.6°F is at the high end of normal, not an exact mean, and that “normal” body temperature is more accurately around 36.8°C (98.2°F) for contemporary adults 7. This early finding hinted that our baseline temperature might have drifted downward since Wunderlich’s era.

Subsequent research has strengthened this observation. In 2002, a systematic review examined 20 different studies of normal body temperature conducted between 1935 and 1999 4. This meta-analysis found the average oral temperature across those studies was ~97.5 °F – more than a full degree Fahrenheit lower than 98.6°F 4. (The review also emphasized that factors like measurement technique and patient demographics influence reported values 4.) Likewise, a 2017 study analyzing over 35,000 British patients (with ~250,000 temperature readings) reported a mean oral temperature of 36.6 °C (97.9 °F) 8 4. These findings from large 20th-century and early 21st-century datasets consistently suggest that typical body temperatures today hover in the 97–98°F range, rather than exactly 98.6°F.

The most direct evidence of a true historical decline came from a 2020 study by Stanford University researchers (Protsiv et al.), which explicitly tested the hypothesis that human body temperature has decreased over time. This study, published in eLife, combined data from three distinct cohorts spanning 160 years 4:

- Civil War Veterans (1860–1940): Medical records from 23,710 Union Army veterans (with temperatures taken in the late 19th to early 20th centuries).

- National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey I (1971–1975): Data from 15,301 people in the 1970s U.S. national survey.

- Stanford Clinical Data (2007–2017): Electronic health record data for 150,280 adult patients seen at Stanford in the 2000s.

In total, the team analyzed over 677,000 temperature measurements across these periods 8. Crucially, they adjusted for differences in measurement technique and demographics, and also examined trends within each dataset (to control for thermometer technology changes) 8 8. The results showed a clear downward trend: average body temperatures have fallen by about 0.03 °C per birth decade 3 3.

In practical terms, men born in the early 19th century had mean body temperatures approximately 0.59 °C higher than men today, and women’s mean temperature has decreased by about 0.32 °C since the 1890s 3 3. These differences translate to roughly 1°F lower average body temps in the 2000s compared to the 1800s. The Stanford study found that the current average oral temperature of adults is around 36.4–36.6 °C (97.5–97.9 °F), whereas it was about 37°C (98.6°F) in the 19th century 2 4. Notably, the decline was monotonic (steady across time) and was evident even within the Civil War veterans’ cohort over their lifespans, which makes it unlikely that the trend is an artifact of changing instruments or protocols 3 8. In short, multiple lines of evidence – from controlled 20th-century studies to large-scale historical comparisons – indicate that the “normal” human body temperature has indeed decreased by about 0.5°C (1°F) since the 19th century 4.

Evaluating Study Methods and Findings

The studies above employed a range of methods, all strengthening the case for a true decline:

- Wunderlich (1800s): Measured axillary temperatures with then-state-of-the-art thermometers; enormous sample size but all from one region. He reported a single mean without statistical distribution details 6, so later scientists questioned how precise 37.0°C was.

- Mackowiak et al. (1992): Prospective measurement of healthy volunteers’ temperatures at set times. While the sample was much smaller, it was tightly controlled and used modern thermometry, yielding a lower mean (36.8°C) and highlighting variability 7.

- Sund-Levander et al. (2002): Systematic literature review of 20 studies, capturing different populations and methods over decades. This provided a broad consensus that average oral temps ~36.4°C and also detailed normal ranges by site (e.g. axillary readings running lower) 9.

- Obermeyer et al. (2017): Big-data analysis of a UK primary care database, with 35k patients and repeated measurements. This “real-world” approach found an unequivocally lower mean (36.6°C), although it was a cross-section of recent times and did not itself prove a temporal change 8.

- Protsiv/Parsonnet et al. (2020): Historical comparison across eras. By uniting 19th-century, 1970s, and 2000s data, this study directly tested for a trend over time. The large sample and internal consistency checks (looking at birth cohorts and adjusting for age, time of day, etc.) lend strong credibility to its finding of a true physiological decrease in baseline body temperature 3 8. While it is an observational study (we cannot literally go back and measure people in 1860 with today’s tools), the authors took care to rule out obvious confounders like instrument calibration differences. The consistency of the decline across independent datasets is compelling.

Taken together, these studies consistently find modern “normals” below 37°C, and the best evidence (the 2020 Stanford study) confirms a historical cooling trend in average body temperature.

Possible Explanations: Why Are We Cooling Down?

If humans today truly run cooler than a century or two ago, what might explain this change? Researchers have proposed several, not mutually exclusive, reasons. Most hypotheses center on changes in our overall health status and living environment that have occurred since the 1800s, which could affect our basal metabolic rate and thus body heat production.

1. Reduced Chronic Infections and Inflammation: The leading explanation is that modern populations have far less burden of chronic infection and inflammation than in the past. In Wunderlich’s era, low-level infections were common: for example, in the mid-19th century approximately 2–3% of the population lived with active tuberculosis at any given time 4. Endemic illnesses like TB, syphilis, malaria, parasitic infestations, and poor dental health (leading to gum disease/abscesses) meant that many “healthy” people actually had chronically elevated inflammatory activity. Wunderlich himself noted that a great number of his patients had diseases that would raise body temperature 4. By contrast, advances over the last 150 years – improved sanitation, vaccines, antibiotics, and public health measures – dramatically reduced the prevalence of chronic infections. The authors of the 2020 Stanford study explicitly point to higher standards of living and hygiene leading to fewer persistent infections (like tuberculosis and periodontal disease) as a key factor in lowering the population’s average metabolic rate and temperature 4. In essence, we’re healthier now, so our bodies can run “cooler.” When the immune system is not constantly activated, the body doesn’t have to sustain as high a resting temperature.

Is there evidence to back up this idea? Some comes from observing groups with heavy infection burdens. A study of the Tsimané, an indigenous forager-horticulturalist population in Bolivia, provides a revealing example. The Tsimané have historically had high exposure to parasites and infections. Researchers found that fighting infections took a measurable toll on their metabolism: elevated white blood cell counts and parasitic infections were associated with a 10–15% increase in resting metabolic rate in this population 10. This corresponds with higher baseline body temperatures – essentially, every 1°C increase in body temp is estimated to require about a 10% increase in metabolic rate 2. Moreover, even in that remote population, average body temperature has been declining in recent years (2004–2018), presumably as access to medical care improved and infection rates fell 2. These findings support the notion that chronic inflammation/infection elevates body temperature, and relieving that burden (through better health) can lead to a cooler baseline. Dr. Julie Parsonnet, the Stanford study’s senior author, has argued along these lines: “Inflammation produces all sorts of proteins and cytokines that rev up your metabolism and raise your temperature,” she notes, so a reduction in inflammation could explain lower body temps today 8. In short, our bodies may not have to work as hard fighting microbes day-to-day, allowing our resting temperature to fall.

2. Comfortable Modern Environments (Thermoregulation made easier): Another major factor is the modern ability to control our ambient environment. Widespread use of heating and air conditioning, improved insulation, and warmer clothing means that people today spend most of their time in a thermoneutral zone – an environment that doesn’t force our bodies to expend extra energy to heat up or cool down 2 4. In the 1800s, people routinely endured cold bedrooms in winter or sweltering homes in summer, which would trigger the body to boost metabolic heat production (or sweating, etc.) to maintain 37°C internally. Now, we keep our living and working spaces around ~21–23°C (70–74°F) year-round. Parsonnet and colleagues suggest that this reduced thermal stress on the body has likely contributed to a lower basal metabolic rate 2 4. Our internal “thermostat” doesn’t have to run as high when the surrounding environment is consistently comfortable. Even the simple fact that we can stay warm with less shivering (thanks to better clothing and heating) or cool with fans/AC could translate to a slightly lower average body temperature over time 2.

3. Changes in Body Size and Lifestyle: Humans have changed in other ways since the 19th century. We are, on average, taller and have higher body mass (both lean and fat mass) than our ancestors. Metabolically, a larger body might produce more absolute heat, but also dissipates heat differently; some scientists have speculated that increased body mass (and obesity prevalence) could paradoxically lead to feeling warmer yet having a lower measured core temperature due to heat dissipation issues – though this link is not clearly established. Additionally, a more sedentary lifestyle (less manual labor, more sitting) might reduce overall metabolic tone. The Stanford team did adjust for BMI and found the temperature decline persisted 3, so body composition is likely not a primary driver. Still, lifestyle and physiology today differ from the 1800s in myriad ways (diet, stress, etc.) that could subtly influence our baseline temperature. Parsonnet admitted “we don’t really know what [these changes] mean in terms of health, but they’re telling us that we are changing” 2.

In summary, the most plausible explanation for cooler modern body temperatures is improved health and lower chronic inflammation, coupled with living in more temperature-stable environments. These factors together allow our resting metabolic rate to be a bit lower 8 4. It’s important to note that the 2020 study did not pinpoint an exact cause for the drop – their data showed the pattern, but determining causation relies on reasoning and auxiliary evidence 2. The hypotheses above are supported by logical and some empirical evidence, but they haven’t been proven with a controlled experiment (which would be impractical over 150 years!). Nonetheless, experts find them convincing. As one science writer neatly put it: “Lower metabolic rates, thanks to improved public health, may be behind the decrease” in temperature 4 4.

“Normal” Body Temperature: Changing Definitions Over Time

The definition of a “normal” body temperature – and the threshold of fever – has evolved along with these findings. Historically, Wunderlich’s work gave birth to the idea of a standard normal temperature, but even he intended it as an average with a range. Over time, medical guidelines have shifted from citing a single “normal” value to emphasizing ranges and individual baselines.

Wunderlich’s Era (mid-1800s): Based on his extensive measurements, Wunderlich defined normal body temperature as around 37°C, with typical fluctuations between about 36.2°C and 37.5°C in healthy adults 3 4. He recognized that no one constant temperature applies to every person at all times – normal varies by hour of day and person. He also set an early benchmark for fever: about 38°C (100.4°F) and above was considered febrile 5. Interestingly, this threshold is a bit higher than some modern fever definitions, likely because his measurements were axillary (underarm) which run slightly cooler than core temperature 11. In textbooks of the late 19th century, it became common to quote “37°C or 98.6°F” as normal body heat (sometimes with the qualifier “about” to hint at variation) 6. The concept of “blood heat ~98°F” was already in use before Wunderlich, but his data cemented 98.6°F as the canonical normal 6.

20th Century Medical Literature: Throughout the 20th century, 98.6°F remained entrenched in medical teaching and public knowledge – but medical professionals increasingly acknowledged that normal temperature encompasses a range. For example, a 1960s or 1970s nursing or medical textbook would still list 37°C as the standard, but also note the normal diurnal variation of roughly 0.5°C 11. By 1990, the textbook Clinical Methods stated: “Normal body temperature is considered to be 37°C (98.6°F); however, a wide variation is seen” 11. It described how an individual’s daily temperature can vary by up to 0.5°C, with early morning lows and evening peaks, and emphasized that this circadian rhythm is consistent for each person 11. The text also gave differences by measurement site: rectal temperatures run about 0.3–0.5°C higher than oral, while axillary temperatures run ~0.5°C lower than oral 11.

When it came to defining fever, late-20th-century guidelines were already a bit more conservative than Wunderlich’s 38°C axillary rule. Clinically, fever is often defined as an oral temperature above ~37.5°C (99.5°F), or a rectal temperature above 38.0°C (100.4°F) 11. In other words, an oral temperature between 37°C and 37.4°C (98.6–99.3°F) might be considered the high end of normal, whereas crossing 37.5°C begins to be viewed as low-grade fever. This aligns well with Wunderlich’s range – remembering that his 38°C “upper normal” was for axillary readings (approximately equivalent to 37.5°C oral) 11. Thus, even as 98.6°F was taught, physicians understood that normal ranges roughly span 36.5°C to 37.5°C for oral temperature in an adult 6.

One illustrative example: a 1992 editorial in JAMA noted that Mackowiak’s new data (mean 36.8°C) did not actually overthrow Wunderlich’s legacy but refined it – normal body temperature was always a range, and 98.6°F was simply one point in that range 12 12. What did change is how strictly the exact number is regarded. Doctors began to recognize that many healthy people never reach 98.6°F, and some always run a bit higher or lower normally.

21st Century and Current Guidelines: Today, medical references and health authorities define “normal” body temperature more flexibly than ever. It’s common to cite a range of normal for oral temperature, often something like 36.1°C to 37.2°C (97°F to 99°F), rather than a single number 1. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and other agencies continue to use 100.4°F (38.0°C) as a convenient cut-off for fever in screening (e.g. for infections), which is essentially unchanged from older definitions. What has shifted is the awareness that the average person’s baseline may be a bit below 98.6°F. As reviewed above, large studies in the 2000s found averages around 97.5–97.9°F 1 4. Many recent articles – both in medical journals and popular science outlets – explicitly state that 98.6°F is likely too high as an average for modern healthy adults 1 2. For instance, a 2020 Stanford study press release flatly said, “Our temperature’s not what people think it is… what everybody grew up learning, which is 37°C, is wrong” 8 8. A 2023 editorial from Harvard Health Publishing posed the question, “Time to redefine normal body temperature?”, noting that 98.6°F “may not, in fact, represent the best estimate of normal body temperature” given new data and that normal body temperature may be falling over time 1.

In practice, clinicians now focus less on an absolute “normal temp” and more on changes from an individual’s typical temperature and the presence of symptoms. As infectious disease physician Aimalohi Ahonkhai explains, “There’s no one number that means a fever, and there never has been. If you’re way warmer than what’s typical for you, let your doctor know. But if you’re cooler than you expected, that may just be the new normal.” 4. This encapsulates the modern view: “normal” is a range, and context matters. Even Wunderlich in 1868 would have agreed – he wrote of fever as an elevation above one’s usual daily pattern, rather than strictly above a universal cut-off.

To compare across time: 19th-century doctors introduced the 37°C average and used ~38°C as a practical fever threshold, 20th-century medicine retained 37°C as a reference point but acknowledged a normal range and set fever at ~37.5–38°C, and 21st-century experts highlight that the true average is slightly lower and that normal varies individually. The core definition of normal body temperature is thus shifting from a fixed number to a population distribution (approximately 36.5–37.5°C for healthy adults, now possibly centered closer to 36.6–37.0°C) and even toward a personalized concept of normal.

Conclusion

Over the past two centuries, the scientific understanding of human body temperature has come full circle in some ways. Carl Wunderlich’s 19th-century monumental study established 37°C as an approximate normal value, but also taught us that normal varies by person and circumstance. In the years since, we enshrined “98.6°F” in textbooks, only to have modern research remind us that normal is not a single static number. Careful analyses of historical and contemporary data show that the average human body temperature has declined by about 0.5°C (1°F) from the 1800s to today 4. The reasons likely include improvements in public health – fewer chronic infections and inflammatory conditions – and changes in our environment and lifestyle that reduce metabolic demands. As a result, the midpoint of “normal” is a bit cooler now than before.

In medical practice, this means that while 98.6°F is not “wrong,” it is better seen as the high end of a normal range rather than an exact norm for everyone. Modern healthcare providers define normal temperature broadly and pay attention to individual baseline changes. The concept of normal body temperature continues to be refined with new data: what hasn’t changed is the fundamental insight from Wunderlich’s era that human temperature is variable, and understanding its patterns is key to detecting illness. The past 160 years have simply taught us that those patterns can shift with the times – and indeed, our “new normal” may literally be a degree cooler than it was for our ancestors 4.

References

- Time to redefine normal body temperature? - Harvard Health: https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/time-to-redefine-normal-body-temperature-2020031319173

- Parsonnet, J. et al. (Stanford University School of Medicine) Press Releases and Commentary on body temperature studies (2020–2023) (Are Human Body Temperatures Cooling Down? | Scientific American) (Body temperature: What is the new normal?). – Discussions of potential causes (reduced infections, metabolic changes, climate control).

- Wunderlich, C.A., Das Verhalten der Eigenwärme in Krankheiten (Leipzig, 1868); translated as On the Temperature in Diseases (1871). – Historic study defining 37°C normal (axillary) from 25,000 patients ( Decreasing human body temperature in the United States since the Industrial Revolution - PMC ) (Average Body Temperature Takes A Dip | Discover Magazine).

- Wunderlich, C.A., Das Verhalten der Eigenwärme in Krankheiten (Leipzig, 1868); translated as On the Temperature in Diseases (1871). – Historic study defining 37°C normal (axillary) from 25,000 patients ( Decreasing human body temperature in the United States since the Industrial Revolution - PMC ) (Average Body Temperature Takes A Dip | Discover Magazine).

- Carl Wunderlich • LITFL • Medical Eponym Library: https://litfl.com/carl-wunderlich/

- Human body temperature - Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Human_body_temperature

- Mackowiak, P. et al. “A Critical Appraisal of 98.6°F… and Other Legacies of Wunderlich,” JAMA 268:1578–80 (1992). – Found mean 36.8°C in healthy subjects, questioning 98.6°F (98.6°F - JAMA Network).

- Obermeyer, Z. et al. “Individual differences in normal body temperature: longitudinal big data analysis,” BMJ 359:j5468 (2017). – Big-data study (UK) reporting ~36.6°C mean, reinforcing lower modern normal (Body temperature: What is the new normal?).

- Normal oral, rectal, tympanic and axillary body temperature in adult men and women: a systematic literature review - PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12000664/

- High resting metabolic rate among Amazonian forager-horticulturalists experiencing high pathogen burden - PMC: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5075257/

- Temperature - Clinical Methods - NCBI Bookshelf: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK331/

- The Charmed Life of 98.6°F - The American Journal of Medicine: https://www.amjmed.com/article/S0002-9343(25)00057-9/fulltext ↩